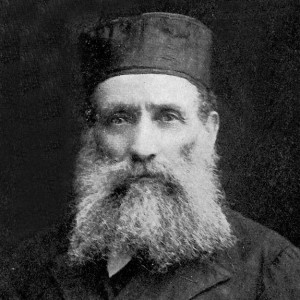

Herbert Cantor

July 20, 1913 – September 21, 2000

Herbert Cantor, 87, of Levittown, New York, died on September 21, 2000, following a brief illness. A good, kind man, smart and funny, he was much loved by Millie, his wife of 54 years, children Phil, Mady, and Danny, children-in-law Carrie, Arthur, and Laura, and grandchildren Max, Nate, Tess, Eli, Ethan, and Alice.

A World War II veteran and lifelong Democrat, he owned Valley Stream Auto Parts for 30 years, and was a member of the Israel Cantor Family Society which was founded at his birth. A passionate follower of the events of the day and a partisan of fairness and decency throughout his life, he leaves a legacy of devotion to family and friends, of generosity without strings, and a marvelous sense of humor. He will be missed.

Obituaries by:

Eulogy

by Daniel Cantor

a son

I’m not really sure how to give a eulogy. My friend Aaron said to me yesterday, it’s not so much that you don’t know what to say, it’s that you don’t know what not to say. My secret hope is that if I talk about my father I can bring him back to life, and we’ll get another chance to enjoy him.

The occasion today may be my father’s death, but that’s just an excuse. This is about honoring and remembering his life. I know I speak for my mother and sister and brother when I say that we are tremendously grateful for the love and goodwill expressed over the last month by so many people. Some of you knew Herb for decades, others crossed paths with him more recently, but it’s pretty clear to us that whenever people met my father, they were always struck by what a kind, decent man he was. My grandmother Tessie—Herb’s mother-in-law—used to call him “a regular prince.” And he was.

Herb Cantor was born in 1913, on Amsterdam Avenue, at home. His parents were immigrants from Eastern Europe, and, like so many others, they were poor, though—he often liked to remind me—so was everybody else and they never felt impoverished in any meaningful way. He was the youngest child of Solomon and Anna—Shlomo and Nachama—and he had five adored and adoring older sisters: Rose, Spo, Edith, Lily, and Minna. The surviving children of his sisters are all here today, and I don’t think I’m exaggerating to say that Herb loved each and every one of them–and worried about them–as if they were his own children.

The story is told in our family that Herb’s paternal grandfather–Israel Aaron–was so elated at the birth of this grandson that he climbed onto the kitchen table and danced a jig. This, despite having only one leg.

Herb’s birth, or more accurately his bris, was the occasion of the founding of the Israel Cantor Family Society. It was a cousins club, in Yiddish a landsmenschaften, and it was a focal point of family life for what was a very large family. Herb’s father was one of 22 children, 13 of whom survived to adulthood, and he had scores of cousins. The fact that the Society continues to exist and now has third, fourth, and even fifth cousins as members, was a source of great pride and pleasure to my father.

He grew up in Manhattan and Brooklyn and the Bronx, and graduated from Morris High School in 1931—not an auspicious time for a young man to be entering the labor market, and the years of the Depression imprinted themselves deeply on Herb. He took any job he could find and went to night school, first at Brooklyn College and later at Fordham Law.

One job he found, in 1932, played an important role in his life and deserves some mention. He became a runner on Wall Street–a messenger, really, for Lehman Brothers. It was there that he met two other young men–teenagers really—Milton Gold and Marvin Penner, and these three fellows began a friendship that lasted another 68 years. The friendship endured the Depression, the War, and even the centrifugal forces of suburbanization.

In recent years, the three men would get together now and again to have coffee in New York, maybe take in a museum, and basically spend several hours shmoozing. I’d ask him what they talked about, and he would say–everything and nothing. I think they all just reveled in each other’s company.

Marvin died on September 1st, and Milton died on September 4th, and Millie says that once Milton died she knew Herb wasn’t going to make it. Milton’s son-in-law said they had a secret pact. Maybe so. After Herb died I came in on a conversation Mady and Phil were having about how the three friends were probably in a coffee shop now. I wasn’t sure what she was talking about, and I said, “You mean, like they’re in heaven.” And she said, “Yeah. But it’s really just a coffee shop.”

I think she’s right. Herb’s idea of heaven was to visit with the people he loved.

Anyway, the Depression ended. The War started. And Herb enlisted in the Army a few weeks after Pearl Harbor. He joined the Signal Corps, as it was considered a good place for Jewish soldiers, and he went to basic training in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Thanks to one of his sisters, Herb knew stenography—now there’s a lost skill—and this got him a job as a secretary to a colonel.

It was while stationed in Fort Monmouth that he had the great good fortune of attending a Jewish folk dancing social, and there he met a young woman named Mildred Block. Millie had recently been recruited away from the British Purchasing Agency by the Signal Corps Labs, who wanted girls who had some college math. She moved to Fort Monmouth from Brooklyn to take a job testing communications components. It was her chance, as she put it the other day, to do something for the war effort and maybe meet a nice fella. Personally, I’m glad she won on both fronts.

Herb shipped out in mid-1943, and spent the next two years in India, Burma, Ceylon and China. He didn’t make a big tsimmes out of his years in the Army–for him it was the right thing to do, and he did it. His two old friends were both Conscientious Objectors, but this did not cause a break among them, which I think showed great character and loyalty on Herb’s part.

Herb rose to tech sergeant and was discharged, honorably, late in December 1945. He married my mother two weeks later. This marked the beginning of the next stage of his life, really the next stage of Herb and Millie’s life together, because from here on out they were partners. They started a family, figured out how to earn a living, left their one-room apartment in Long Beach for what seemed to be an absolutely palatial 4-room house in Levittown in 1948. Dad was working for his brother-in-law Ed, Steve’s father, at Ed’s auto parts shop in Lynbrook. He had to provide for a growing family, and earlier ambitions of lawyering or politics were put aside.

Phil was born in 1950, Mady in 1951, and I arrived in 1955. In that same year, Herb–who at this point was not all that young and certainly had many responsibilities–took a chance and went into business for himself. He found a partner–a hardworking machinist named George Schutz–and in December 1955 they opened Valley Stream Auto Parts, otherwise known as “the store.” It was the center of Herb’s working life for the next 30 years, and he made it into a successful business.

I’m still in awe when I think about it. He left the house before we were even awake, and came back after 7 every night, and worked every Saturday as well. And not once did he ever complain.

I don’t think that my Dad loved his job, but I do know that he loved his family. And he was willing to work as hard as necessary to support us. My brother believes, and I think he’s right, that Herb enjoyed being a good and honest businessman, and was tremendously proud of being a provider for his family. He was also one of a dying breed–a liberal small-business owner. When all of the auto parts workers on Long Island went on an industry-wide strike, at the Valley Stream shop Herb was the one who gave out the leaflets.

The business grew slowly but steadily over the years. Herb was well aware of the long boom that he was riding as part of the automobile industry and often commented on how lucky he was. He did not mistake his good fortune for virtue and was always utterly sympathetic to people who hadn’t had such luck. He instinctually favored the underdog. He was a dyed-in-the-wool, FDR New Deal Jewish liberal Democrat, and one has to mourn the passing of yet another such person. My sister insists that Herb would want me to encourage everyone to vote in November, and to vote on Row H. Mady also insists that Herb intends to vote by absentee ballot in November. I’m not quite sure how this’ll work, but I’m sure she has a plan.

For me, one enduring daily memory from childhood is Dad walking through the front door and the family sitting down to dinner, which always included a discussion of current events. I think my father read a newspaper, often two newspapers, every day of his life from the late 1920s to the year 2000. The New York Times has never had a more loyal reader. And the Levittown Tribune never a more acute critic. That was our local weekly paper. In Herb’s immortal words, it was the only paper he could read in its entirety on the way to the bathroom.

In 1985, Herb sold the store to two of his employees and retired, and thus began the final chapter of his life. He was lucky in retirement, and he knew it. He was healthy, and he had enough money for his extremely extravagant lifestyle. Phil and I used to meet him in the City for lunch, and could never get him to take a taxi to meet us. He would only ride the bus, even as he got weaker and walking became harder. Depression-era habits die hard.

The happiest part of his retirement began with Mady’s marriage to Arthur. Herb was exceedingly fond of, and impressed by, Arthur, Carrie, and Laura, and he enjoyed teasing us about how well we had each married. And then in 1986, to his utter delight, his first grandchild, Max, was born in Philadelphia. Herb danced his own jig, and it continued with Nate in 1987, Tess in 1990, Eli and Ethan in 1991, and Alice in 1995. He used to say that he waited a long time for the first grandchild–he was 73 when Max was born–but it was worth it. And for the next 13 and a half years he was a loving, vibrant, and remarkably cheerful presence in all of the grandkids’ lives.

In retirement Dad also began what to us was a most unexpected hobby. He became a court buff. He made friends with several other men, some of them here today, and their group became a fixture at the county courthouse. He enjoyed judging the judges, watching the lawyers perform, and was often very moved by the human stories and drama that unfolded. Newsday did a nice story on the court buffs last spring, which gave Dad a lot of pleasure. And he and Millie have made a little cottage industry of being interviewed by various graduate students, documentary filmmakers, sociologists, and anyone else interested in the history of Levittown’s early days. The Jewish Heritage Archive interviewed him only a few months ago for two hours about his experiences during the war, and that’s a tape I know we will cherish having.

To the very end Herb kept his wits about him. As many of you know, the surgery didn’t go well. But he did regain consciousness for a few days, and was fully aware of us and of what was going on. He couldn’t speak because of vocal cord damage, but he could write and use hand sign language and occasionally puff out a few words. At one point, a nurse fixed his pillow and asked, “Mr. Cantor, are you comfortable?” And Herb, who knew that he was dying, mouthed one of his favorite lines. “I make a living.”

Herb asked me a couple of months ago if I thought he had really had much influence on my life. It was an interesting conversation, and I realize now that perhaps he was sensing the end of his life and wanted just a tiny bit of reassurance. It was freely given. He had many wonderful qualities, but perhaps the one that his children would agree was the most important to who we have become was that he was unconditionally supportive of us throughout our lives. He helped us financially when we needed it, encouraged us professionally in what I know he considered three relatively odd career choices, and never ever second-guessed us. Mady said the other day that Herb fundamentally trusted us and assumed that we would make good decisions for ourselves. And he was right to be confident because he had instilled in us some common sense, some sympathy, and some smarts.

Just three days before his surgery we had an impromptu gathering for Herb in the backyard. It was a great day, with all the grandkids playing and Herb animated and telling stories and making sure we didn’t spend too much on the takeout food. At dinner, this normally reserved man who didn’t express his feelings easily stood up and made the most touching valedictory, telling us that if he didn’t survive the surgery he was nevertheless a satisfied man, and that he loved us all, especially Mom, and that the last 15 years had been the best years of his life.

Of course we said “Herb, what’s the worst that could happen?” which he thought was hilarious. And of course the worst has happened, but I prefer to think about how much he loved a good joke, and what a sweet guy, what a funny guy, he was. I know that Phil and Mady and I always loved introducing both Millie and Herb to our friends, who always seemed to share our delight in them.

I talked on the phone to my dad pretty routinely. He, of course, was from the old school, where the point of a long-distance call–from Levittown to, say, Brooklyn–is to get off the phone quickly, before the charges mount up. This was even more the case when it was my nickel, so to speak, as he didn’t want me or the party to give unnecessary money to the phone company. But I could usually keep him talking for a few moments about political developments, and he always ended our conversations the same way: “I’m proud of you, Danny-boy , I’m proud of you” were always his closing words.

Well, I just want to say that we are proud to be Herb Cantor’s children. He was a good man.

Mady Cantor

a daughter

I want to share with you one small memory I have of my father because I think it speaks to his devotion to his family.

When I was in high school I participated in something called Sports Night, an evening of competitions that took place in a crowded, overheated gymnasium full of screaming teenagers. The whole thing was my father’s idea of hell, and he just could not bear to go to it.

My part was a solo gymnastics performance on the rings. I had just started my routine and was upside down, 7 feet off the ground, when at the far end of the gym, framed all by himself in the doorway, I saw my father, wearing his raincoat, with his hat in his hand, looking very uncomfortable, I’m sure, but he was there. I could always count on his love and support. I never had to earn it. It just came with the territory.

Here is a short poem that I think is about living well and dying well. It reminds me of my father. It was written by Marge Piercy.

Connections are made slowly, sometimes they grow underground.

You cannot tell always by looking what is happening.

More than half a tree is spread out in the soil under your feet.

Penetrate quietly as the earthworm that blows no trumpet.

Fight persistently as the creeper that brings down the tree.

Spread like the squash plant that overruns the garden.

Gnaw in the dark and use the sun to make sugar.

Weave real connections, create real nodes, build real houses.

Live a life you can endure; make love that is loving.

Keep a tangling and interweaving and taking more in,

a thicket and bramble wilderness to the outside but to us

interconnected with rabbit runs and burrows and lairs.

Live as if you liked yourself, and it may happen:

reach out, keep reaching out, keep bringing in.

This is how we are going to live for a long time: but not always,

for every gardener knows that after the digging, after the planting,

after the long season of tending and growth, the harvest comes.

Steve Cotler

a nephew

San Francisco

“The departed whom we now remember have entered into the peace of life eternal. They still live on earth in the acts of goodness they performed and in the hearts of those who cherish their memory.”

My favorite uncle, my Unkie Herb, is gone. Yet he still lives on earth in my heart because I cherish his memory. I cherish his quick wit, often brilliant in its surprising off-hand delivery. Though his gentle ego kept him from demanding applause, he knew that he was a very funny man.

The last time I was at his home, only a month or so before he died, we sat up talking for hours. I was on the couch; he was in his easy chair. I looked up at the wall and noticed a painting of some boats that had been hanging there for as long as I could remember. “Uncle Herb,” I said, “I think it’s time to get a new painting. I’m getting sick of looking at that one.” “I have a better idea,” he replied immediately. “Sit on the other side of the room.”

I cherish his granting me unconditional love… love for a little, loud boy careening through a summer vacation in his home… to a grown man living a life so very different than his own. He came to visit me in San Francisco about ten years ago and sat with me on the trading floor of a very large brokerage firm. After an hour of yelling, ringing phones, and intense communication, he leaned over to me and whispered, “Very hectic.”

I cherish his total commitment to family, which I tried to emulate in my own life. From my childhood to the present, a visit with Uncle Herb was always on my New York itinerary. Often Levittown was my entire itinerary. First would come a quick meal (usually a choice of eight or nine things that Millie just happened to have left over or in the oven). Uncle Herb and I would sit at the table, and he would always begin with, “So, what’s new?” His joy in

the adventures and triumphs of others was unfeigned.

I brought my children into his home. And just as I had done, they careened past his easy chair, bouncing against his NY Times, a daily ritual which was his university and his continuing education. He was clearly and unequivocally an intellectual. In a fairer world he would have been a scholar; in an earlier world such a scholar would have been a Talmudist.

He was always in good humor; I never met a man who complained less. He was always interested, always willing to engage in conversations.

At restaurants, he would study the menu, then ask Millie, “What do I like?” This was not helplessness; it was the luxury of being taken care of… as Millie did so well.

Theirs was a marriage that worked—for over 50 years. He knew her strengths (and there are many), and he enabled her to make a true home… always open, always comfortable. They were a couple who talked to each other, who not only loved each other… but also really liked each other.

Over the last two years, Uncle Herb and I had several long and personal discussions. We spoke about his youth, and I pleaded with him to write down or dictate some of his stories. He demurred, protesting that little of his life was worth memorializing… and some things are better left unrecorded.

So, I asked him what his dreams had been when he got out of the Army. “I had no dreams,” he said. “I only wanted a job… any job.”

But he did have a dream. He dreamt of building and supporting a family. And he dedicated his life to that dream. And it did come true. His family is here today. And the great worth of his life lives on in their hearts… their hearts that cherish his memory.

In the winter, when all is dark and cold, the memory of Herb Cantor’s love and warmth remains alive.

Jean Nordhaus

a niece

Washington, DC

The last time we were together with all the Cantors was on a happy occasion, Max’s Bar Mitzvah, and now, here we are.

Herb and I spoke maybe two or three times a year at best, though always with great joy on both sides, or so Herb made me believe—but I suspect he made everyone he greeted feel the same way, that he was absolutely delighted to see you.

So Herb’s death won’t change my day-to-day life, since we saw one another so rarely, but it changes the shape of my world unalterably. He was the last link between our world and the world of his and my mother’s childhood, a world we needed to understand in order to understand our own. If I wanted to know something about our grandfather, whom I never knew, or our mother as a child, I would always call Herb—or Herbtl, as my mother and her sisters called him. So, when Mady called to say things weren’t going well after the operation, I wanted to call out, “Hang on, Herb, because there’s so much more we need to ask you.”

When our mother was dying, the young rabbi who visited with us sent me, after his visit, a translation of a poem by the great Hebrew poet, Chayyim Nachman Bialik. I’ve kept it hanging above my desk for the past ten years, and now I’d like to read it for Herb.

The poet has written:

After my death, mourn me thus:

There was a man, and, see, he is no more.

Before his time, his life was ended

and the song of his life was broken.

O, he had one more melody,

and now that melody is lost forever,

lost forever.

Carrie Cantor

a daughter-in-law

spoken at the shiva

The truth is, I’m feeling both sad and happy today. I’m sad because Herb, my father-in-law, is gone from our day-to-day lives. I’m sad that Herb won’t be sitting in his usual place at the head of the table. I’m sad for the empty spaces that seem to be everywhere all of a sudden.

But I’m happy too. Happy that Herb was born on that summer day in 1913. Happy that he survived two world wars and the Depression. Happy that he found Millie and loved her his whole life. Happy that he raised three wonderful children—one of whom I had the privilege to marry. Happy that he was fascinated and engaged by the world around him and enjoyed all that life had to offer. Happy that he was loved and cherished by so many people. Happy that Herb led the sort of life that makes us all so sad to see ended.

Goodbye, sweet Herb.

Originally published in Newsday, September 24th, 2000 edition

Herbert Cantor, One of First Levittown Homeowners

by Katie Thomas

Staff Writer

Herbert Cantor, a retired auto-parts store owner who was one of the original Levittown homeowners, died Thursday of complications from open-heart surgery.

He was 87.

Cantor was born in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, but later moved to Harlem, graduating from high school in 1931-an unlucky time to be thrown into the working world, said his wife, Mildred Cantor.

It was the beginning of the Great Depression, and “there weren’t any jobs,” she said.

In 1933, he was able to find steady work as a Wall Street “runner,” getting paid $5 a week to transport documents from one brokerage firm to another.

While working his day job, Cantor was attending night school. He graduated from Brooklyn College with a bachelor’s degree in the mid-1930s, and continued at Fordham University’s law school, earning a certificate in law a few years later.

For the next several years, Cantor struggled to help support his family, working several odd jobs. His law background was nearly forgotten. “You did whatever you could,” Mildred Cantor said. “In those days you didn’t have a career, you had a job.” In 1941, Cantor enlisted in the Army, starting out as a private in the Signal Corps, the division in charge of communication. Cantor was first stationed in Fort Monmouth, N.J., which is where he met his wife, who had a civilian job there. When he was discharged in 1945, he held the rank of technical sergeant.

In 1946, Cantor married Mildred. The two settled in Long Beach, in a one-room apartment, Mildred Cantor said. Cantor began working in his brother-in-law’s auto-parts store.

In 1948, they moved to the newly built Levittown. “We thought the Levitt house was a little palace,” Mildred Cantor said. “To have four rooms was a luxury.” There, the couple started a family, raising two sons and a daughter. In 1955, Cantor opened his own business, Valley Stream Auto Parts. He ran the store until his retirement in 1985.

About eight or nine years ago, Mildred said, Cantor rekindled his interest in the law, but this time as a spectator. Along with a half a dozen other “court buffs,” Cantor spent nearly every day watching high-stakes trials in Nassau Criminal Court and at the federal courthouse in Uniondale.

“I was getting a first-hand report from him every night at the dinner table,” Mildred said.

Cantor was a member of the Suburban Temple in Wantagh, and the Israel Cantor Family Society, an association of 150 of his relatives.

In addition to his wife, Cantor is survived by children Philip Cantor of Montclair, N.J., Mady Cantor of Philadelphia, and Dan Cantor of Brooklyn. He is also survived by six grandchildren.

The funeral services will be held today at noon at the I.J. Morris Funeral Home in Hempstead. Burial will be at the Mount Judah Cemetery in Queens.

Shiva

The family will be sitting at home in Levittown through Wednesday, September 27, from 3–8 pm.

Phil will be at Montclair on Thursday, September 28 from 4–8 pm

Mady will be at Philadelphia on Sunday, October 1 from 5:30