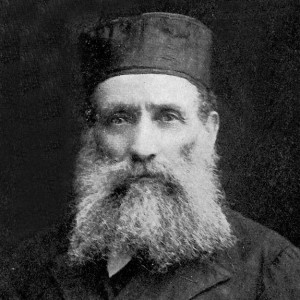

Arthur

Liebersohn

February 9, 1951 –

February 29, 2012

Eulogies

- Daniel Cantor, brother-in-law

- Joseph Liebersohn, brother

- Harry Liebersohn, cousin

- Bruce Duffy, boyhood friend

- Tess Liebersohn, daughter

- Max Liebersohn, son

- Dennis O’Donnell with a poem

- Philadelphia Inquirer obituary

- Family photos of Arthur

Eulogy

Daniel Cantor — March 4, 2012

Brother-in-law

Arthur Liebersohn was born in Washington DC on February 9, 1951. He was the youngest of David and Bertha Liebersohn’s four children, after the arrivals of Joe, Hope and Yona. He grew up in Chevy Chase, Maryland, and after high school, he left for the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where he studied economics. The indifferent high school student was all of a sudden invigorated by the life of the mind and got serious about academic work in college.

Mady recalls how Art seemed to remember everything he ever read. Material from courses he took forty years ago was as fresh as books he read last month, whether the topic was the wars in the Balkans or the history of Prohibition. Art knew a ton about Prohibition, no doubt because it combined three of his favorite topics: counter-productive social and economic policy, corrupt local officials and police, and… beer.

He graduated from Wisconsin in 1973, at the height of the anti-Vietnam War movement. He had a middling draft lottery number, and was concerned, but Harry told him they’d never get to him. Harry was right, luckily. And probably it was lucky for the Army too. It’s hard to picture Arthur blindly following orders that he thought were stupid.

In the fall of 1973, he moved to Philadelphia to attend law school at Penn. Both of his parents—the Liebersohn side and the Roseman side—had roots here, and after graduating in 1976, he never left. Arthur did not follow the path that most young Ivy League-trained lawyers take, however. He didn’t migrate to a big law firm, head to Wall Street, enter government service, or even work for Legal Aid. He was very much a public interest lawyer, but on a path he made for himself. In fact, Arthur never had a boss in his life. Whether it was because he wanted the freedom that that allows, or because he suspected that employers might not find his stubbornness to be overly endearing, Arthur worked on his own for 35 years. On his own, but surely not alone.

As friends gathered at the hospital since last Saturday, it became clear that he shared more than just office space with some wonderful colleagues over the years. He was enmeshed personally and professionally with an enormous number of people over the decades, many of whom became dear friends. He and Rick Freeman had lunch together a thousand times, and Arthur enjoyed each and every one. Josh Rubinsky recalls how he continued to call Arthur for advice on bankruptcy issues long after he was no longer in the Cherry Street office, and Arthur “always knew what to do, who to talk to, where to get various pleadings, who the players were, and above all would tell you who you could trust.”

Not long after graduating from law school, Arthur had the great good fortune to meet Lance Haver, Lee Frissell, Susan Marcus and above all, his great mentor, Max Weiner. Lance tells a wonderful story about how they learned that there was a young lawyer who had just finished at this fancy law school, and he was willing to work for free! Good organizers, they made a bee-line for him, and thus began a lifetime of collaboration and friendship.

In CEPA—the Consumers Education and Protective Association—and later in the Consumer Party, Arthur found his political and even spiritual home, and of course it started him down the professional path that he never left. The idea of CEPA was simple but profound: Capitalism can be pretty nasty; poorer people especially get screwed; and while you think you might be able to fight back with legal strategies, in fact what you really need to do is organize. And so he, and they, did.

They saved the homes of people facing Sheriff sales, sales that would of course been unnecessary if Arthur’s friend Steve Ebner had won his election to Sheriff. But Steve didn’t, so CEPA stayed vigilant. They would force unscrupulous car dealers to compensate customers who had been cheated, with a simple but effective strategy. The aggrieved consumer and CEPA leaders, no doubt frustrated with inaction, would arrive en masse, set up a picket line, and enter into negotiations from a position of strength. Arthur liked those actions, but his real brilliance was as a strategist who combined legal and organizational approaches. Working with another lawyer named Henry Sommer, Arthur developed a theory, novel in American history and ultimately accepted by the court, that changed bankruptcy law in a case about—of all things—furniture. The details are complicated, but it required both legal and organizational smarts. Arthur had both. Not long after he got involved in CEPA, Max Weiner and his brain trust launched the Consumer Party.

Arthur served as the Campaign Finance Chair of the Party for more than two decades, and was responsible, says Lance, “for keeping us all out of jail.” He never took a dime for this, of course. Arthur liked to pretend that he was a cynic, and in a sense he was. He was cynical about the pious and phony myths that keep people down. He was cynical about the stated good intentions of, say, your average credit card company. But he was not at all cynical about the people he wanted to serve. No cynic spends a career doing what Arthur did. As his friend Rick Freeman wrote the other day, he was “a friend to the poor.” Not out of noblesse oblige, but out of a very righteous anger. Perhaps it’s better to think of him as a skeptic. Mady called him “a joyous skeptic” the other day. I think that’s right. He was unsure, to say the least, that justice and reason would prevail, but he always hoped that it would. If you read yesterday’s Inquirer, you know that Arthur ran for elected office several times. In the 1978 race for Philadelphia District Attorney, which included Ed Rendell as the Democratic nominee, Arthur got asked how could he possibly be a DA given his lack of prosecutorial experience. Always quick on his feet, Arthur responded that it was a badge of honor that, quote, “I’ve never beaten a confession out of anyone.”

In 1979, in a very interesting and important moment in Philly politics, Arthur did the work to get on the ballot in the Mayoral race, all the time knowing that he would end up standing down in favor of a more prominent candidate, Lucien Blackwell, who was a great labor and civil rights leader. Arthur did not require the spotlight, and was willing to do the background work that makes democracy and civic life possible. Lance told me that Arthur saw his electoral campaigns as a chance to teach people about the true cost of poverty, about the reality of economic crime. Arthur may have represented a “minor” party, but his confidence and eloquence made it impossible for his rivals to marginalize him. Indeed, a few years later, when he was the Consumer Party’s statewide candidate for Attorney General, he received the endorsement of the Philadelphia Daily News. This was almost certainly the only time in the 20th Century that a major newspaper in Pennsylvania endorsed a third-party candidate for Statewide office.

In 1990, he became a Trustee in the US Bankruptcy Courts which, as he pointed out at many family gatherings, were enshrined in the Constitution. He joined the board of CBAP—the Consumer Bankruptcy Assistance Project—to help low-income citizens who could not afford to file for bankruptcy. In both roles, he tried to be fair and use law in the service of decency and social fairness. Judge Frank of the Eastern District Bankruptcy Court was quoted in yesterday’s paper: “There aren’t many lawyers in town with a deep understanding of the bankruptcy laws. There are even fewer who can match the commitment Arthur demonstrated to poor people and ensuring that the legal system treats people who pass through it in a fair and respectful manner.”

He was intellectually curious, and fascinated by debt. Debt is what makes civilization possible, he said. He was the first (and only) person who ever explained to me what a collateralized debt obligation was, and no doubt he could have made a lot of money working the other side of the street. But that would not have fed his soul. What did, was to provide pro bono tax preparation assistance, year after year, at the VITA sites run by 1199C for their members and other working class people in Philadelphia. He liked to say – “Some people have ski season. I have tax season.” Saturday after Saturday during tax season over the last 9 years, Arthur would go to the VITA site and help people prepare their tax returns, and lately he would check the work of the other volunteers to make sure everyone was getting what they were due. He even got Tess to help him, and she served as a “greeter” during her high school years. Cheryl Feldman says he simply loved the work. You can close your eyes and see him talking, interacting, hearing about their lives, making a material difference, getting someone enough of a refund for a security deposit on a better apartment. You can see him altogether enjoying himself.

So while Arthur relished his role as the designated curmudgeon, the truth is, he was immensely dedicated to helping others and making structural change in our society. He liked structural alternatives. And he joined them all. He was a member of every co-op he could find: Project Learn, where Max and Tess went to school. A fuel oil co-op. Beachcombers. Weaver’s Way Food Co-op. And perhaps the most complex of all, the Wissahickon Babysitting Co-op. Arthur was the intellectual author of the Cheesecake Rule, and it deserves some explication. This was the rule that the parents leaving the house needed to leave some cheesecake behind for the sitter. But of course the crucial question was, how much? If the parents left a full cheesecake, the sitter would be unwilling to eat any, as the nibbling would not go unnoticed. And if the parent left too little, then the sitter’s guilt at finishing off the cheesecake would likewise prevent any indulging. Arthur’s fix was to have parents leave two-thirds of a cheesecake in the fridge, so that the sitter could eat a lot if the situation required it, and the parents would never quite remember if they had left one-third or two-thirds behind, and so would not be dismayed upon returning. This is pure Arthur. Mindful of human nature, and determined to make things work out fairly. Plus, he must have been delighted to create a rule with such a great name.

Arthur was one of those people that everyone liked. He was the glue of the far-flung Liebersohn clan. And he was a wonderful addition to the Cantor family. Mady’s parents—my mother and father—just adored Arthur. We spent decades of Thanksgivings and Passovers together, and because he knew a good line was worth re-using, they always ended the same way: “Danny,” he’d say as one or the other of us left, “I just want you to know that you’ve been like a brother-in-law to me.” More vintage Arthur.

Of course, throughout all these many years, towering above all else in his life was his immense love for and devotion to Mady, and then to Max and Tess. He was a good husband, and attended more dance concerts than, well, anyone. He was a wonderful father, and took great delight and pride in his children. He adored them both. Max said something yesterday that stuck: “We didn’t get enough of my dad. But of course, you never could.” Max is right. We didn’t get enough of Art, but what we got was pretty darn great. He was smart, he was funny, and he gave back to his community and his family in ways large and small. It was a life well-lived, and he will be missed.

Memories of Arthur Liebersohn

Joseph Liebersohn, brother

I’m Art’s older brother, Joe Liebersohn. Almost every one has experienced Art’s help, advice and seen his ability to work effectively with a broad range of people. I‘ve know him for longer than most people, and would like to talk a bit about his younger years, and share a few memories.

After he was born our mother had a lot of errands to run. For the next few years I became his baby sitter. I dressed him, fed him and changed his diapers — yuk.

When he was ten I took Art and his cousin Harry on a short walk, along the railroad tracks to a railroad trestle. They were excited and said they were just like Davy Crocket and would blaze new trails. After ten minutes, the rocks, bushes and weeds were too much. They wanted to go home. Their big achievements would come when they were older.

When he was a teen, and into his 20s, each year Art went with us on a summer vacation, to a cabin at Deep Creek Lake in Western Maryland .

Our kids learned a lot from Art. They had never seen a man with a pony tail who wore one red sneaker and one white. Here are some of the things he did.

Towed by a boat, he roared by and showed them how to fall off water skis, over and over again. How to swim across the lake through speed boats with rarely a close call. Then there was his vaudeville dance routine on the dock, where he always fell into the lake. They learned about horseback riding safety when we all went riding and he took his horse thorough some trees and was knocked off. He chased the horse all the way back to the stable.

Then the final lesson. He went over a high waterfall, sliding over rocks on his butt, and didn’t break a bone. Don’t try these stunts at home.

But on to more recent years: Arthur was deep into Philadelphia politics and once got me involved. He was running for mayor and as usual, corruption, nepotism and cronyism were big issues. The mayor had placed his brother Joe as Director of the philly fire department. In one speech Art went after corruption and said that when he was elected he would avoid nepotism and never put me, his brother Joe, in as Director of the fire department

Arthur was always there to help and support me. His advice was always helpful. As Art used to say to me— Joe, you’ve been like a brother to me. Art, I am so sad you are gone. You will always be my brother.

For my cousin and older brother…

A speech I never expected to write

by Harry Liebersohn, cousin

Some of you have said to me at one time or another that Arthur and I were like brothers, and it’s one of the kindest and truest things that you could say. I would just add that Arthur was like an older brother to me. Early memory of this: One time I was upset with him, I think because he had just clobbered me at Monopoly, and to calm me down he offered to teach me how to cheat at poker. Older brotherly love knows no greater offer.

What I want to talk about today, though, is some of the things that made him what he was. The first one is the paint store that his father David (or Homer) and my father Myer owned and ran together at 1014 Seventh Street in Washington. It was the place where all the ethnic neighborhoods of the city jostled together, black, southern white, Chinese, Italian (gone except for AV’s Italian Restaurant) and Jewish—gone except for the small store owners like our fathers. Arthur’s father was a handsome man with a fine gentlemanly side, and my father had a master’s degree from Penn, but they felt at home in the paint store, and they expected us to feel at home there too.

It wasn’t just any paint store. Arthur and I would take gallon cans of white paint that our fathers had bought for cheap, mix in colors, add the label “Myer’s Supreme,” call it Hawaiian Pink or Mountain Green, and put it out front for $2.50 a gallon or whatever the going price was.

Sometimes our customers were suburban ladies, but most of the business came from one of the strangest and crustiest group of characters you’ll ever meet: painters, contractors, apartment house owners, men with spattered hands who smelled like sweat.

One time a few years ago, Arthur said to me, “You know, the paint store was the only thing that saved us.” Of course, I knew just what he meant. It saved us from the suburbs. It saved us from the fifties. It saved us from the bland and homogeneous world that you see in nostalgia dramas like Mad Men. Washington was a segregated city in the 1950s and early 1960s, but at the paint store we worked alongside George and Leonard, the two African-American men who worked there, and we knew the lovely neighborhood grandmas and the painters who were regulars in the store.

It didn’t make us perfect; but from the time we were little, it was enough to break the bubble of Chevy Chase and Silver Spring .

That was one side of Arthur. You had to know him better to see another side: he read books, always, going way back. He read 1984 first and I followed. We thrilled together over Catcher in the Rye and he read on to Frannie and Zooey. That was in junior high. In high school I discovered Proust and gave Swann’s Way to Arthur, who read it too. A special favorite was The Great Gatsby: Jay Gatsby’s grandeur entertained us and moved us. And that brings us back to Arthur’s moral qualities. Gatsby is a story about social pretension and the inner hollowness of the privileged. That was the conclusion Arthur came to about them as well. It could have been different. He was a smart dresser in high school, he was always funny, he had physical courage, and lots of girls were interested. But all the dating and partying was just high spirits; Arthur never bought into the game of the pretentious classes. He had, we had, the paint store to remind us that there was another and actually a more interesting world out there.

One final word. Arthur never stopped being my older brother. One time when thanks to Dorothee we were living in Princeton for six months, he came up and said, “Where do you hide all of the poor people around here?” Best comment I’ve ever heard on the place. I always turned to Arthur for advice and it was always good. One time after I asked him what to do about a bureaucratic tiff, he said, “Don’t be a victim!” –best advice ever, I’ve tried to take it to heart. At this moment, which I never dreamed I’d experience, I still can’t believe that he won’t be there to guide me as he did for almost sixty years.

A Boyhood Friend

Bruce Duffy

I’m very honored to have been asked to speak today by the Cantor/Liebersohn family. A family I’ve been a part of for nearly 50 years. In fact, I saw Arthur not two months ago with his cousin Harry. Arthur looked great—then gone. Gone in a way that seems almost unbelievable to me. And let me tell you why.

The story begins in first period in home room. 7th grade in Kensington Junior High School in 1964. It’s the story of a bluff, world-weary boy to whom normal rules did not apply. Because the Arthur Liebersohn I knew then, at 12 and 13, well, he was way too cool to die or follow the rules. Rules! Rules were for fools.

No indeed, you would not see hormonal 13-year-old Arthur P. Liebersohn wearing some tacky, rumpled shirt that tumbled out of the dryer. He wore starched, pressed shirts. As for those shoes with the dangerous looking toes, well, they weren’t just shoes. They were Florsheims. Handbuilt. $50 a pop…

Yes, to me, my new sidekick was Steve McQueen. Batman. James Bond, too. And then like Halley’s comet—this.

Okay. So much for the story of the mythic Arthur Liebersohn. I now want to turn to the deeper story of how Arthur changed. Arthur’s second act, if you will. The story of his reinvention.

Let’s face it. Along with our good self, we all live in some way with a shadow self. A troubled self who periodically visits like a bad relation. We all have our trouble.

For Arthur—in my opinion—the real trouble started when he was around 17. His father, David, developed cancer. Swift, ravaging cancer. I know because, more than a few times, I helped Arthur carry his helpless father down the stairs to the living room—a terrible thing for a son to see up close.

But Arthur’s detour didn’t end there. A couple years later his irrepressible mother, Bertha, she too died. And so in his early 20s, Arthur was an orphan. On his own. Something he affected to not much care about. But of course he did. Visible in a sharper edge to his natural cynicism.

But you know what: life has a funny way of redeeming us—swapping sorrow for luck. And Arthur’s luck is plain to see. It was marrying Mady Cantor. And being adopted—overwhelmingly—by Cantor family. People who, safe to say, revolutionized Arthur’s views on love and family, life and politics. And fatherhood, too, with Max and Tess. A love in which he flowered as a man.

Yes, for me, Arthur will always be a James Bond/Steve McQueen kind of character. But what is more important, in his second act, Arthur Liebersohn became a full-blown soul. An expansive one loved by many. And a man who will be deeply missed.

Goodbye, buddy.

Remembrance from a Daughter

Tess Liebersohn

My father always said, “Tess—you can do three things when you turn 40: get a driver’s license, get married, and attend my funeral.” Even though he was 19 years early on the last event, I understand where he was coming from. He didn’t want me to grow up, but I did, with him as the perfect role model.

He used to say “Aren’t you embarrassed of me? Aren’t kids always embarrassed by their parents’ shoes?” On the contrary, I was far from embarrassed of him or his shoes. In fact, I bragged about him all the time—his eccentric yet illustrious political career, his wit, his jokes, his knowledge of history, his ability to get into free artistic events, even the fact that he called me Tessticle Messticle.

I bragged about the fact that his serious heart surgery in 2005 didn’t stand a chance against his sheer will to get back to the better parts of his life—my mother, work, biking and the consumption of earthly pleasures in general. When I visited him in the hospital after the surgery, I didn’t know what to expect. I found my father, looking normal except for a new scar. He was excited because his room had a huge window which overlooked the old Philadelphia Civic Center and he took great joy in watching it be torn down. He taught me that no matter where you are, there’s always something interesting to look at.

During my time in Pittsburgh, we spoke on the phone several times a week. It was usually when I was walking to class, so the conversations rarely lasted beyond 10 minutes yet I hung up every time with some new bit of information or advice. Our conversation topics were rather technical: taxes, cars, why the media is all lies, paranoia, and half-truths, and the proper way to load a dishwasher. In our last conversation, we talked about how it was a beautiful day on both sides of the state. We talked a lot in the too-short time I knew him. That’s why this was rather easy to write. He gave me so much material for love and appreciation.

Of my father’s many one-liners, one that has always stuck with me is “Wherever you go, there you are.” Like any soon-to-be graduate, I don’t exactly know where I’m going, but I know who I am. I am my father’s daughter. Max and I are the luckiest kids in the world to have called him Pop for as long as we did.

Remarks on the Passing of my Father

Max Liebersohn — March 4, 2012

A few years ago, I spent some time thinking about my father‘s role in my life, all the way back to childhood, and I realized Pop did many things that (at least I would think) a parent should do, regardless of how much I grumblingly went along with them at the time. His activities involved a regular experience of nature, with countless long treks through the Wissahickon and Valley Green, and physical fitness, on countless bike rides. He gave me incredible, loving support, something I thought about whenever I heard friends detailing the awful and antagonistic relationship with their fathers. He was indescribably hilarious. Kind, charming, devoted.

Pop had a certain combination of wit, intelligence, capability, and deftness that I’ve seen in very few people and always admired. Someone to turn to. And beyond that was his humanity: his warm, world-weary, comfortable self.

No one lives forever, although to keep ourselves sane (and actually live our lives) we ignore it.

I’d thought about my father’s health many times. Worried about it. He’d beaten Death on the operating table, took a fall on his bicycle, felt unusually tired after a long car drive. In the back of my mind, ever current, his health seemed to lie unsteadily on his past problems—sometimes these thoughts came to the forefront, and I was overjoyed to see him, knowing how valuable it was—he was strong, hardy, he lived the best life he could. So while I understand how he could be gone too soon, it still felt and feels like a shock: too soon.

Arthur Philip Liebersohn, my father, was a wonderful and memorable man. His voice, his appearance, his personality, all are so vivid to me. He’s gone physically, so the memories of him (and the people touched by him) are what I have left. He was one in a million: I’ll likely never meet anyone like him again, and I’m both grateful and enriched for all the time we had together. The world is poorer without him.

Box Wine and Tablecloths

a poem by Dennis O’Donnell

The man sure knew how to throw a picnic.

Forget hampers crammed with fried chicken,

watercress sammies or the like,

a true picnic thrown by our host

first and foremost

called for a sturdy box wine.

Or box daiquiri, box colada, box margarita,

or perhaps you’d prefer a splash of canned champagne,

with a straw?

In any event, portability

was the key,

because a proper picnic site

was attained by bicycle alone.

And a proper libation

required just the right

saddlebag, front pack, or pannier

for its carriage, but no worries:

You name it, he had it.

And on arrival

– this picnic table, not that one,

closer or further or sunnier to suit the ladies –

there would be neither food nor drink

for the weary traveler

without the laying of the tablecloth.

Unfurled with a flourish,

it was as if it could cover the world,

not least cedar planks,

scorched grass or concrete slabs.

Just as our host always did,

the proper tablecloth

centered our attention

on the pleasures at hand,

brought focus to our folly,

brightened even the merest morsel

or dullest bean salad.

Just as our host did

wherever he went,

the cloth brought a certain courtly charm,

and made a statement:

We had arrived at this place,

made special only by our presence,

our sharing it with each other,

and our host.

As he always said:

Wherever you go, there you are.

And there we were,

at a table-clothed picnic

and in his hands.