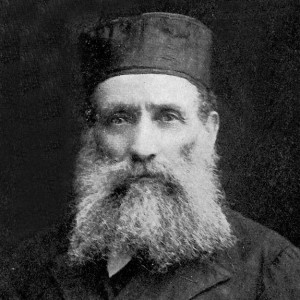

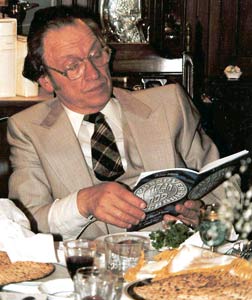

Joseph Hornick

April 22, 1918 – November 9, 2002

Eulogy by Sandy Hornick

I don’t really know how to eulogize my dad, and in talking to my brother and sister I’m aware of impressions and memories we share and others we hold uniquely. One way I remember dad uniquely is his teaching me that patience is a virtue, so I wanted to remember my father today by some of his traits, ones that would be high on anyone’s list of virtues: Perseverance, Family, Loyalty, Responsibility, and Faith.

My father had to persevere almost from the beginning of his life. Early on, his life was threatened by a severe case of scarlet fever, in an era before antibiotics. Yet he found the strength to survive. In the hard times of his youth, he had to help with the candy store or with his dad’s super’s responsibilities.

I don’t want to suggest dad was the perfect child. In one of the stories that for some strange reason we didn’t hear until we were adults, dad was confronted with an unwanted glass of milk that he was obligated to drink. This problem he solved brilliantly by pouring the milk in the drawer with my grandmother’s starched curtains.

He learned at an early age of his hearing loss. And while my brother and I grew up thinking that grown men answered the phone with the earpiece pointed at their chests, I periodically would think he was sometimes isolated by his hearing loss, especially in group settings. (For those under the age of 50, old hearing aids had a large amplifier worn around the chest).

My father wanted to go into the air conditioning repair business, correctly perceiving that this would be a growth industry, but he could not afford the $300 tuition. Instead he went to work for nothing as an apprentice to learn the upholstering trade. When he finally got paid, he spent his first paycheck, not on himself, but on new furniture for his parents.

Dad knew his life was picking up when he picked up a beautiful young waif of a girl on the beach in Coney Island. I’ve always been a little confused about the story that mom and dad’s first date was to his sister Francis’s and my uncle Ben’s wedding, trying to imagine bringing a first date to such a significant event with the extended family. But I think dad knew from the start that he had met the person he would call at the end of his life, “my best friend” and who would call him, “the love of my life.”

He went into the upholstery business for himself in 1945, co-founding Fairchild Furniture in the former T & W. Saratoga theater, a charming and endlessly fascinating dump of a building that still stands in Brownsville. The business would go through good times and hard, and though the living room furniture business largely left New York for cheaper locations, dad kept it going for forty-three years. In the process, he provided employment for his mother and my uncle Ben and others and provided lifestyle for his wife and children that had been unimaginable when he was growing up. He also provided the couches and chairs for many of you who have joined us today.

Dad kept that business going by working virtually endlessly. When he woke us to go school, he had already been up for hours doing the business’s paper work. He would then work until six or seven or eight at night making furniture and then load up a couch, love seat and two side chairs on top of, and in the trunk of, a 10-year old 1952 Chrysler and drive to Monticello and back. Ever the child of the depression, after returning home late at night he would often pass up the day’s now cold dinner for leftovers. After other long days, dad could be found at the synagogue building an ark for the lower sanctuary, making cushions for some charity or, later, at Amy’s house fixing something.

The depression left other marks on dad as well. Shortly after the end of the war, the copper springs used in making furniture were in short supply. Dad found a good buy and stocked up on springs. When he moved from Saratoga Avenue to Chestnut Avenue in 1971, Marc and I discovered a thousand or more pounds of these now dust covered springs on the dirt floor of the Saratoga Avenue basement. Dad wouldn’t hear of throwing them out or even selling them, so Marc and I loaded them into the station wagon and brought them to the new shop. Eventually, the city took the Chestnut Avenue shop for a parking lot and we had to move Fairchild Furniture to Avenue X. To our chagrin, but not our surprise, we had to move every one of those springs again.

He didn’t just work hard in his 20’s and thirties but continued to work day and night at the business until he retired in 1988. Before our own kids were born, Linda and I would sometimes accompany dad on these evening deliveries. They were long drives, on dark roads filled with dad’s stories, usually the same stories, that seemed to always lead to a kosher deli. Young and strong, Linda and I would carry one end of the couch, dad would take the bottom end, with most of the weight, up the stairs. I already miss hearing those stories.

Dad would ultimately provide for his children expensive college educations that he didn’t believe necessary. He never could fathom how all three of his children passed up free educations at the city’s colleges for ones that picked his pocket clean.

But he provided them.

He provided generously for weddings that met his children’s wishes but were more than his simple tastes required.

But he provided them.

And the moment we had children of our own, Grandpa was there to provide for their educations along with a very foolish and out of character sign proclaiming, “I’m the Grandpa.”

Dad started out as a Grandfather with the strange notion that he shouldn’t hold the grandchildren until they were three months old. It didn’t take too long for Meredith to melt that notion away. Dad had to wait along time to obtain the moniker ‘grandpa’ but he relished it and he was blessed to have Amber, Aaron, Jonathan, Chelsea, Eran and Daryl follow in rapid succession. Playing checkers with them or showing them how he could separate his thumb in two or that his name was FINK made him laugh. When dad had his heart attack 14 years ago, he told me he only wished that G-d would allow him to make his grandchildren’s bar and bat mitzvahs. G-d granted him a long life to accomplish most of this wish and his spirit will be with us when we gather to celebrate Daryl’s.

My dad had a strong sense of right and wrong and, I think, a belief that our understanding of the world is imperfect so faith must fill the gaps. I’m here today because of dad’s faith. When the doctor advised my mother to abort a troubled pregnancy, dad trusted his faith and would hear nothing of it.

Dad had a deep and unending commitment to G-d and Yiddishkeit passed down to him by his father and mother and of his responsibility to pass it on from generation to generation. He was active in his synagogue. He sent his children to Hebrew school and taught us by his example.

It may not always have been apparent to the casual observer but dad needed mom and always wanted her around. In their own way, mom and dad gained strength from each other.

It was never more obvious to me than these past five months when we would visit him the hospital or nursing home at a time when mom wasn’t there. He would be agitated when mom wasn’t there and would calm down when mom arrived. Like his own version of the Scarecrow, the Tinman and the Lion, dad new that Amy would keep the doctors on their toes, I would handle the finances and Marc would look after his soul, but it was my mother who provided his courage and his comfort. His last spoken words, clearly spoken, were, “Where’s Mother?”

My parent’s had 59 years together, a virtual lifetime, yet it seems all too short.